Is longtermism helpful?

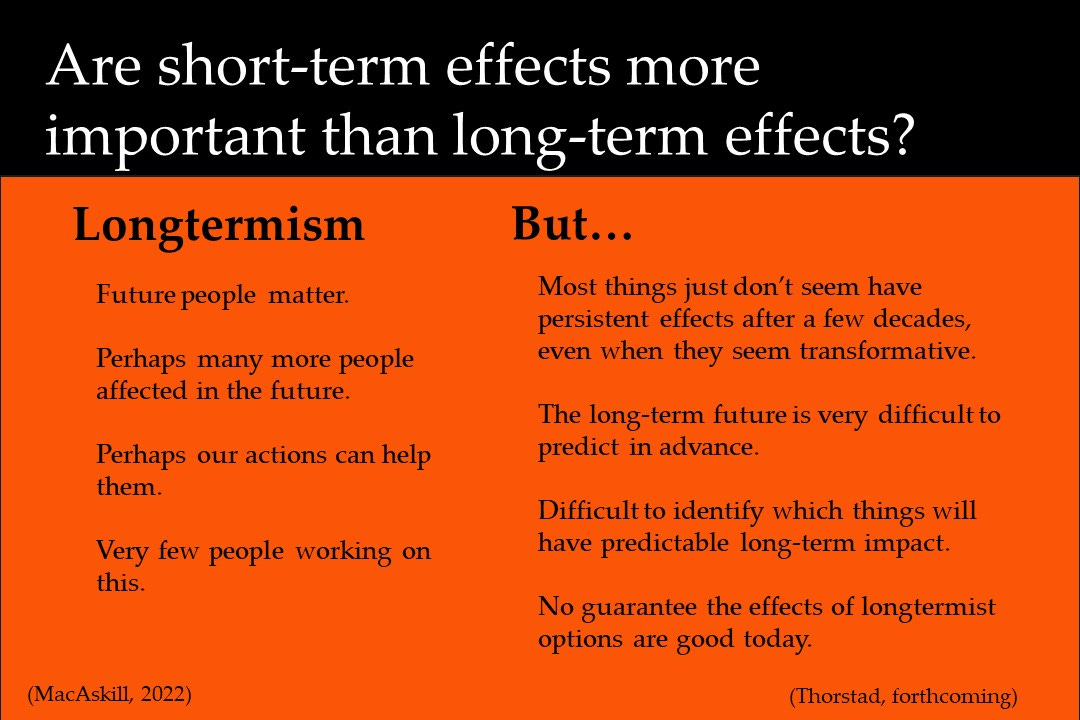

Recent work in philosophy argues for longtermism – the position that often our morally best options will be those with the best long-term consequences. Proponents of longtermism sometimes suggest that in most decisions expected long-term benefits outweigh all short-term effects. In ‘The scope of longtermism’, David Thorstad argues that most of our decisions do not have this character. He identifies three features of our decisions that suggest long-term effects are only relevant in special cases: rapid diminution – our actions may not have persistent effects, washing out – we might not be able to predict persistent effects, and option unawareness – we may struggle to recognise those options that are best in the long term even when we have them.

This is a summary of “The scope of longtermism” by David Thorstad (forthcoming in the Australasian Journal of Philosophy). The summary was first published by the Global Priorities Institute. Rapid diminution

We cannot know the details of the future. Picture the effects of your actions rippling out in time – at closer times, the possibilities are clearer. As our prediction journeys further, the details become obscured. Although the probability of desired effects becomes ever lower, the effects might grow larger. In the long run, we could perhaps improve many billions or trillions of lives. When we weight value by probability, the value of our actions will depend on a race between diminishing probabilities and growing possible impact. If the value increases faster than probabilities fall, the expected values of the action might be vast. Alternatively, if the chance we have such large effects falls dramatically compared to the increase in value, the expected value of improving the future might be quite modest.

Surprisingly, even this might not have large long-run impacts. Studies indicate that just half a century after cities in Japan and Vietnam were bombed, there was no longer any detectable effect on population size, poverty rates and consumption patterns.

Thorstad suggests that the latter of these effects dominates, so we should believe we have little chance of making an enormous difference. Consider a huge event that would be likely to change the lives of people in your city – perhaps, your city being blown up. Surprisingly, even this might not have large long-run impacts. Studies indicate that just half a century after cities in Japan and Vietnam were bombed, there was no longer any detectable effect on population size, poverty rates and consumption patterns.1 To be fair, some studies indicate that some events have long-term effects,2 but Thorstad thinks ‘...the persistence literature may not provide strong support’ to longtermism. There are few established examples of events with persistent long-term effects, there are sometimes alternative explanations for these persistent effects, and these examples tend to be events with large short-term effects as well.3

Washing out

Thorstad’s second concern with longtermism relates to our ability to predict the future. If our actions can affect the future in a huge way, these effects could be wonderful or terrible. They will also be very difficult to predict. The possibility that our acts will be enormously

beneficial does not make our acts particularly appealing when they might be equally terrible. If our ability to forecast long-term outcomes is limited, the potential positive and negative values would wash out in expectation.

Thorstad identifies three reasons to doubt our ability to forecast the long term. First, we have no track record of making predictions at the timescale of centuries or millennia. Our ability to predict only 20-30 years into the future is not great – and things get more difficult when we try to glimpse the further future. Second, economists, risk analysts and forecasting practitioners doubt our ability to make long-term predictions and often refuse to make them.4 Third, we want to forecast how valuable our actions are over the long run. But value is a particularly difficult target – it includes many variables such as the number of people alive, their health, longevity, education and social inclusion. That said, we sometimes have some evidence, and this evidence might point to an act that seems to be slightly more likely to improve the future than ruin it. Even then, our situation is bleak. We only observe a small amount of the evidence that weighs on these issues, and this evidence may mislead. Instead of taking the evidence at face value, we might take it to show that we missed a piece of evidence that would have told us the very same act could devastate the future. Whenever our evidence points towards a specific option that we think will be best for the long term, we may be sceptical that it points the right way.

Option unawareness

Usually, we think of a decision as having a few obvious choices (continue reading, take a break, etc.). This is a simplification. In practice, we often have many options that go unseen (throw shoes out of the window, wear socks on hands, etc.). Longtermism claims that our very best options will be the ones which have the best long-term effects. But in many situations, even if we have an option that has predictably helpful long-term consequences, we may not consider this option while deciding. Also, if we restrict our choice to only those actions we are aware of, we may not readily identify an option with particularly good (or bad) long-term effects. In this way, longtermism might be true for most choices in theory, but false for most of the choices that we actually make in practice.

Conclusion

Overall, these three considerations diminish the scope of the decision situations where longtermism is relevant. In practice, our best options will often be those with the best short-term effects. Although there may be some decisions for which the best option will be one that has enormously good long-term consequences,5 these will be rare exceptions.6

Image by Kama Tulkibayeva.

See Davis and Weinstein (2008) and Miguel and Roland (2011).

For example, the African slave trade’s effect on social trust and economic indicators. See Nunn (2008).

See Kelly (2019) and Sevilla (2021).

This doubt stems from the lack of data, solid theoretical models, and the inherent complexity of the underlying systems. See Freedman (1981), Goodwin and Wright (2010), and Makridakis and Taleb (2009).

Thorstad mentions the Space Guard programme – which checked whether a large rock was hurtling towards the earth – as an example of a longtermist program which avoids his three concerns. Preventing human extinction clearly improves the long-run future, astronomy is incredibly good at predicting things just like this over very long time periods, and we were aware of the option enough to actually do something about it.

References

Donald Davis and David Weinstein (2008). A search for multiple equilibria in urban industrial structure. Journal of Regional Science 48/1, pages 29–65.

David Freedman (1981). Some pitfalls in large econometric models: A case study. Journal of Business 54, pages 479-500.

Paul Goodwin and George Wright (2010). The limits of forecasting methods in anticipating rare events. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 77/3, pages 355-368.

Hilary Greaves and William MacAskill (2021). The case for strong longtermism. GPI Working Paper No. 5-2021.

Morgan Kelly (2019). The standard errors of persistence. CEPR Discussion Papers 13783.

Edward Miguel and Gérard Roland (2011). The long-run impact of bombing Vietnam. Journal of Development Economics 96/1, pages 1-15.

Nathan Nunn (2008). The long term effects of Africa’s slave trades. Quarterly Journal of Economics 123/1, pages 139–176.

Jaime Sevilla (2021) Persistence: A critical review. Supplementary materials for what we owe the future.

Spyros Makridakis and Nassim Taleb (2009). Decision making and planning under low levels of predictability. International Journal of Forecasting 25/4, pages 716-733.